|

Student-created Hundertwasser-style paintings, modeling the way humans and their structures interact with nature and the environment. |

As a new PYP teacher, I find myself returning often to the document Making the PYP Happen (2009). Each time I read this document, it makes more sense to me. During the implementation of the IB PYP Programme standards, principles and practices in the classroom, I learn more about what these principles, practices and standards look and feel like, both from the teacher's perspective and the students' perspective. This week, I am thinking about:

"What adds significance to student learning in the PYP is its commitment to a transdisciplinary model, whereby themes of global significance that transcend the confines of the traditional subject areas frame the learning throughout the primary years, including in the early years." (Making the PYP Happen, 2009).

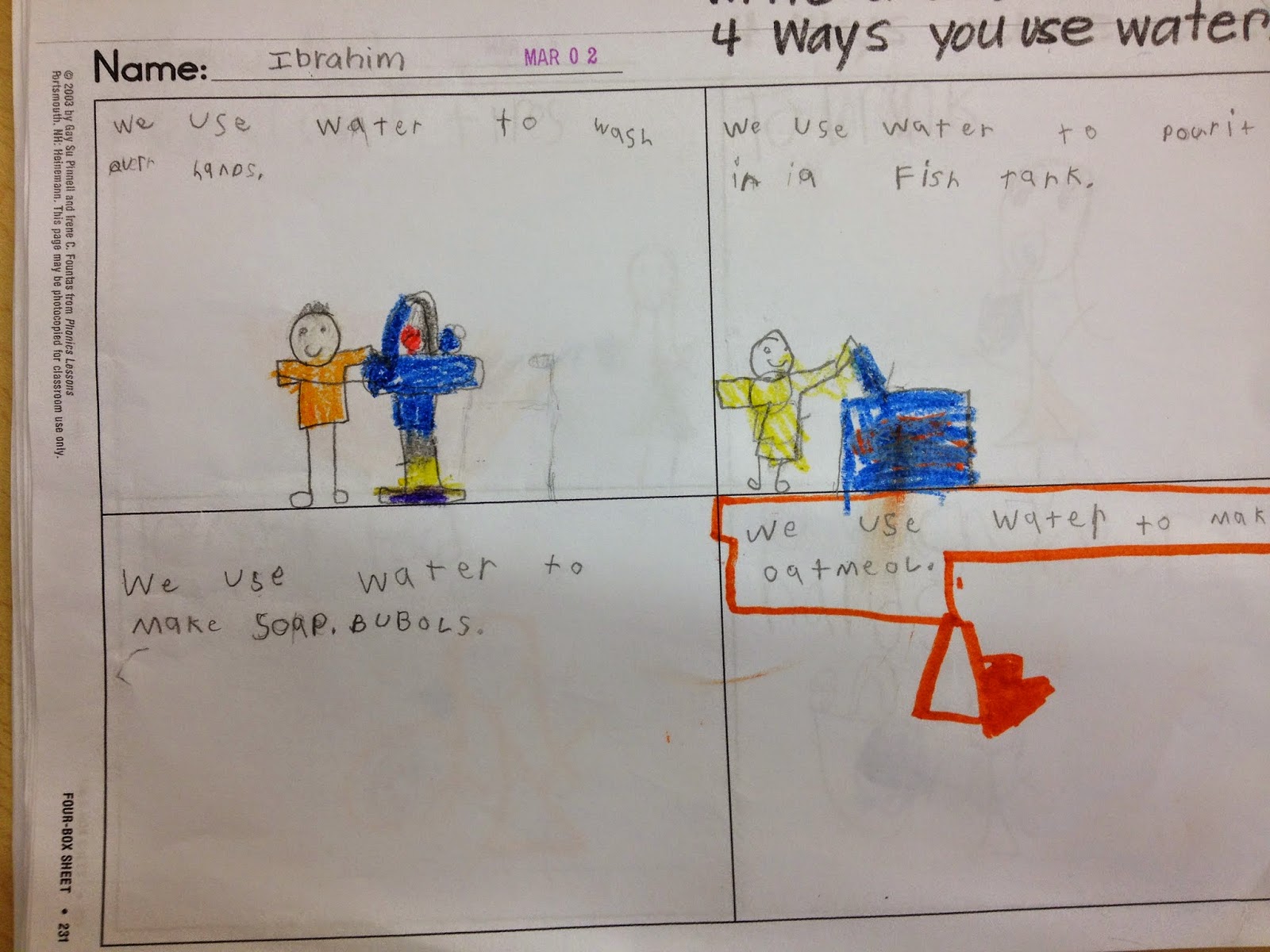

As I work to build student understanding of global mindedness, the commonality of the human experience and multiple perspectives, I wonder about how to help my students think about water and conservation in a more global way. I wonder about how to help them see the common interest humans have in water how much we need water to survive. The unit plan included a number of multicultural folktales that regard water and water sources as magical, and this led us to a discussion about the human understanding of water's essentialness. We also began to explore the idea of sharing perspectives on water, water use and water conservation, not only through stories but in other ways. We talked about different ways humans share their experiences and ideas, including stories, informational texts, art, lectures and digital media. We began to study the artist Friedensreich Hundertwasser, who used his art and architecture to convey messages about the way humans interact with our planet and the importance of our role in caring for it. Some thoughts from Hundertwasser:

"Man is nature's guest."

"If we destroy our roots, we cannot grow."

The transdiciplinary theme of this unit is Sharing the Planet, with obvious connections to curriculum in both Science and Social Studies. Students are exploring where water comes from, how limited this finite resource this is, and how they can impact preservation themselves. There are also the obvious connections to local water conservation groups and other local organizations concerned with water and preservation of our natural water sources. Exploration of the folktales and connections to Hundertwasser help us see both our commonalities with human beings living and sharing this planet, and the multiple perspectives about the desire to preserve and conserve resources.

In this process of learning and teaching, my work is getting closer to transdisciplinary. My students are engaged and they are beginning to learn about the importance of our commonalities with others, and the significance of different perspectives.

|

Hundertwasser-style process: ink then paint. |

|

Exploring Hundertwasser architecture with wooden cubes. |